Illinois’ Franchise Tax: An Archaic Outlier

Illinois’ Franchise Tax: An Archaic Outlier

April 2023 (76.3)

The Taxpayers’ Federation of Illinois has long been an advocate of repealing Illinois’ antiquated and archaic franchise tax. In June of 2019, with much fanfare, Governor Pritzker signed S.B. 689 (P.A. 101-9), phasing out the tax. Unfortunately, in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when concerns for state finances were high, the phase-out was halted, leaving the tax and its cumbersome compliance requirements in place. This article summarizes the history, outlier status, and administrative complications of the Illinois franchise tax.

What is the franchise tax?

The term “franchise tax” can cover a wide variety of tax structures but is usually a tax on corporations separate from the income tax. A few states, like California, use the label for their corporate income tax, but it is typically a tax based on some measure of net worth or capital value. The Illinois franchise tax was enacted in 1872.

The Secretary of State registers and regulates corporations and other business entities and charges an assortment of fees to do so. It also administers and collects the franchise tax. Although revenues from the fees are frequently lumped together with those from the true franchise tax, our focus is only on the tax itself, and not on the activity-based fees.

Illinois’ franchise tax is actually three separate taxes, all based on paid-in capital. “Paid-in capital” is, generally, the money investors pay in return for their shares of stock. It can be funds raised when a corporation issues stock, or through additions to capital (usually subsequent investments by new or existing shareholders), and it can go down when certain corporate transactions occur. Paid-in capital is neither revenue nor net worth; it is the money used to build a business.

When a corporation first registers with the Illinois Secretary of State it pays the first of the three franchise tax components: an “initial tax” on its paid-in capital in the state, at a rate of 0.10%. Each year thereafter, a corporation pays an “annual tax” at the same rate (0.10%). Finally, there is an “additional tax” on increases to paid-in capital, at a rate of 0.15%. The annual and initial taxes have a minimum of $25 and a maximum of $2 million, but the additional tax has no cap. 1 The 2019 legislation phased out all three components of the tax over four years, completely eliminating the franchise tax in 2024, but in 2021 the repeal was repealed.

The 2021 legislation retained the first steps of the franchise tax phase-out. For each of the three franchise taxes (initial, annual, and additional), the first $1,000 in tax due is exempted from tax. As a result, all corporations incorporated or doing business in Illinois must still calculate and file their tax returns, but in many cases, no tax is due.

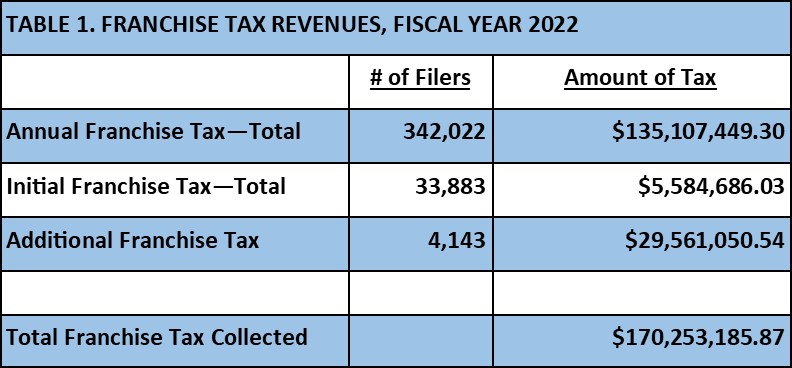

How big is the franchise tax?

The three components of the franchise tax raised $170 million in fiscal year 2022, about 0.34% of general fund revenues (down from 0.41% two years earlier). The corporate income tax raised $5.4 billion. Table 1 shows the number of filers and total revenue generated by the various components of the franchise tax during the fiscal year ended June 30, 2022.

All corporations face the burden of calculating their franchise taxes, no matter their size, but as stated above, the first $1,000 in tax liability is exempt, so many filers end up paying no tax. For example, of the 342,022 corporations required to file an annual report in fiscal year 2022, only 40,502 of them owed annual franchise tax that year. Even so, each of the filers had to first determine whether any tax was due. And, as discussed in further detail below, calculating Illinois’ franchise tax is not a straightforward process.

The franchise tax is a flawed tax.

The five-year economic development plan released by Governor Pritzker in October 2019 contained eight variations of the following statement, a clear recognition that the Illinois franchise tax is flawed and its repeal was (and should be again) a noteworthy accomplishment:

The governor worked with the General Assembly to eliminate the Corporate Franchise Tax, which posed a significantly high compliance burden and penalized businesses for locating or expanding their operations in the state.

The first problem with Illinois’ franchise tax is one shared by all taxes in this category: taxes on net worth, capital stock, or paid-in capital result in pyramiding. In other words, a single investment may be taxed multiple times. It is not unusual for businesses to operate using several legal entities under a parent corporation. This can be for any number of reasons—regulatory requirements, accommodating new investors, or simply a legacy of business expansion. This very common structure frequently leads to a disproportionate franchise tax liability. For example, assume two investors form Company A with $10,000. After a few years Company A expands into a slightly different business, so it forms a new subsidiary, Company B, investing $10,000. A few years later, Company B purchases 90% of the stock of a new venture in the same line of business—Company C—for $10,000. Each year thereafter, that original $10,000 investment is taxed under Illinois’ annual franchise tax 3 times because it is part of the paid-in capital of Companies A, B, and C. If Company A had merely sat on that original investment, or had expanded within the existing corporation, that $10,000 would be taxed only once.

A “good” tax is one that does not pick winners and losers based on artificial differences. The pyramiding problem described above is one way the franchise tax fails this test. Another occurs when debt is used, rather than equity. A corporation financed with more debt, and lower owners’ investments, has lower paid-in capital and thus lower franchise tax liability, resulting in two otherwise identical businesses paying very different amounts of tax. For example, if the owners of Corporation X take out $1,000,000 in personal loans and then invest the funds in the Corporation, its paid-in capital will be $1,000,000. Conversely, if the owners of Corporation Y invest $10 in the Corporation, but it borrows $1,000,000 (guaranteed by the owners), it will have the same $1,000,000 to operate its business as Corporation X, but will face a much smaller franchise tax liability.

Using paid-in capital as a proxy for the benefit (or value) owners receive from incorporation, which was the original justification for Illinois’ franchise tax, makes little sense. Owners are protected from the corporation’s liabilities, but amounts invested are at risk. The more a corporation’s owners have paid in, and therefore the more paid-in capital it has, the more the owners stand to lose. All else being equal, the value to owners of a business’s operating as a corporation decreases as paid-in capital increases. Franchise tax liability, however, increases.

Illinois’ franchise tax has its own unique quirks, making it an outlier even among the few states still imposing this kind of tax, and adding to its policy and practical failings. As discussed in more detail below, Illinois does not use net worth or any standard measure of corporate value as its tax base; Illinois taxpayers must instead track and maintain separate calculations solely for the purpose of paying this tax. Likewise, the apportionment method used for multistate corporations to determine what portion of their tax base (paid-in capital) is taxable by Illinois is different from that used for Illinois’ income tax, and from any apportionment method used for any other state’s tax, needlessly increasing the administrative burden associated with complying with this tax. And finally, Illinois’ franchise tax is administered by the Secretary of State rather than the Department of Revenue, which means separate filings, separate due dates, and a separate administrative regime.

What do other states do?

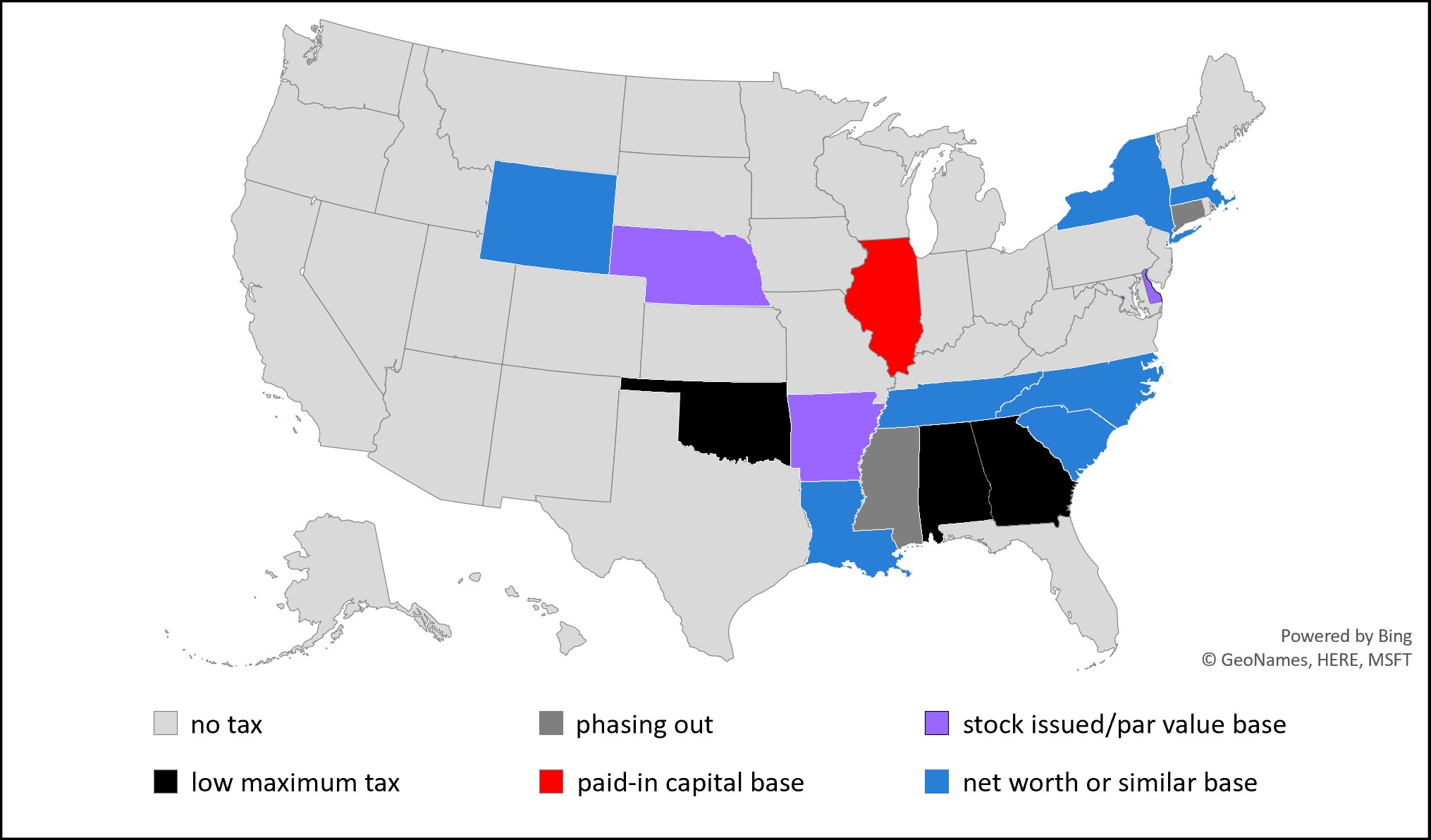

Franchise taxes are rare. While most states charge corporations an annual fee to operate in their state, and nearly every state taxes a corporation’s profits under its corporate income tax, Illinois is one of only a few states to tax corporations based on a measure of their net worth, capital stock, or paid-in capital.

The map below shows the sixteen states that currently impose what can broadly be called franchise taxes. Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and West Virginia have all repealed similar taxes in recent years. Of the sixteen:

- Connecticut and Mississippi are in the process of phasing out their taxes;

- Arkansas, Delaware, and Nebraska base their taxes solely on the number of shares issued and par value of the stock, a very ministerial calculation, rather than on the value of the entity or its capital; and

- Three states have relatively low maximum tax liability (Alabama ($15,000), Georgia ($5,000), and Oklahoma ($20,000)), effectively making them graduated annual filing fees.

Of the remaining eight, seven (Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Wyoming) all use a more traditional base when calculating their taxes—total assets or net worth as reported on an entity’s books and records or on its federal income tax return.

In other words, Illinois is an outlier among outliers. Its unique methodology requires businesses to keep separate records, and means the Illinois Secretary of State cannot leverage off of other taxing bodies (the IRS, Illinois’ Department of Revenue, or other states’ tax departments) when verifying a return’s accuracy.

STATES WITH FRANCHISE TAXES IN 2023

Has the franchise tax outlived its usefulness?

At the time the franchise tax was enacted, corporations did not pay a corporate income tax. The franchise tax was a way for corporations to pay for the relatively new legal protections granted them by the state, and paid-in capital was one of the few possible bases for the tax.

Today the situation is different. Corporations are subject to a wide variety of taxes, including the much more substantial corporate income tax. On the other hand, the administrative and policy flaws associated with the franchise tax are significant, and apply even when no tax is due. The Illinois General Assembly was right to begin the phase-out of the tax in 2019, and the Governor was right to celebrate that accomplishment. We should reinstate the repeal of this flawed tax that has minimal revenue benefit to the State.

Footnote:

1 See 805 ILCS 5/15.35 through 15.45 and 15.65 through 15.75, all part of the Business Corporations Act of 1983, for the relevant statutory provisions regarding the imposition and calculation of the franchise tax.