PTAB: Struggling to Remain Afloat in a Sea of Appeals – Mike Klemens

PTAB: Struggling to Remain Afloat in a Sea of Appeals

September 2018 (71.8)

Mike Klemens[1]

KDM Consulting

The Illinois property tax comes in for lots of criticism. A comparative study of property tax administration in each state and several foreign countries, The Best and Worst of International Property Tax Administration: C0ST-IPTI Scorecard on State and International Property Tax Administration, gave Illinois a C- grade. One bright spot was the ability of property owners to go to the state Property Tax Appeal Board (“PTAB”) to get an independent review of their assessment, and in that aspect of the report Illinois got an “A” grade.

However, those who represent property owners in tax disputes point to the significant delays in resolving PTAB cases as a problem both for property owners whose relief is delayed and for taxing districts that have to pay refunds for multiple years of taxes. In fact, since 2004, each of PTAB’s biennial examinations by the Illinois Auditor General (seven consecutive reports, covering 14 years) has contained the identical finding: “The Board did not allow for the speedy hearing of all appeals.” To make this determination, the Auditor General pulls a sample of cases and calculates how many have not been resolved within one year—its definition of “speedy”. In its 2016 report, the Auditor General sampled 40 cases and found that 21 had been open more than a year, ranging between 378 and 2,021 days.

Illinois Property Tax Administration

The “Best and Worst” study of property tax administration is done periodically by the Council On State Taxation, an organization that represents multi-state and international businesses, and the International Property Tax Institute, an education and research organization. The latest study was done in 2014 with another due this fall. Illinois ended up tied for 38th on their scale, certainly not the best but also not the worst, with the seven lowest scoring states earning grades of D or less.

The Scorecard gives grades in three general categories. Those categories and Illinois grade in each are:

(1) Transparency, Illinois = C

(2) Simplicity & Consistency, Illinois = C, and

(3) Procedural Fairness, Illinois = D.

Within the three broad categories there are 17 subcategories. Illinois got 2 “A” grades. One for not taxing intangible property and one for allowing de novo appeals to an independent tribunal – the Illinois Property Tax Appeal Board. The study’s preferred appeal process would have an initial appeal to the assessor or a review board and a subsequent appeal to an independent tribunal where the property owner can get a fresh review of the matter, and both parties may provide additional evidence not provided at the initial appeal (the legal term is de novo.) Illinois got an A because its Board of Review/PTAB appeals exactly match that process.

PTAB Overview

The aspect of the Illinois property tax system that earned it the “A” grade – the “de novo” review that allows property owners and local assessment officials to start from scratch after the county level appeal – naturally slows decisions. Parties need time to file evidence and to respond to what the other side has filed, extending the process of arriving at a decision. In the typical case of a taxpayer seeking an assessment reduction, the property owner has 30 days following a Board of Review determination to file an appeal with PTAB. The Board of Review then has 90 days within which to respond, but as PTAB staff note, extensions are often requested by Boards of Review, delaying a decision.

PTAB was created in 1967 to provide a place for taxpayers to challenge property tax assessments, initially limited to the 101 counties outside of Cook. A taxing district can also go to PTAB seeking an increase in an assessment it believes to be too low. A property owner seeking an assessment reduction can be represented by an attorney or can represent herself or himself. PTAB operates under rules that are less formal than those used in a courtroom, but it can still be daunting for a lay person. A significant change that PTAB notes over the years is that when they started, taxpayers represented themselves in 90 percent of cases; today 90 percent of cases are represented by an attorney.

If the assessment reduction being sought exceeds $100,000, the property owner is required to notify taxing districts by certified mail. Those taxing districts then have the option to intervene in the case. According to data from PTAB, in roughly 40 percent of the large dollar cases, taxing districts choose to be intervenors, another factor that can slow the process.

An appeal to PTAB is by no means a guarantee of an assessment reduction. For Assessment Years 2013 to 2015, the latest three years where the appeal process is largely complete, taxpayers saw reductions in 7,178 of the 19,361 PTAB decisions issued. That’s a 37 percent success rate for property owners.

For the same 2013-2015 period, more cases were settled by agreement between the parties, 25,074 according to PTAB data. In virtually all of those cases the property owner saw a reduction. PTAB has enacted rules that encourage settlement.

One other aspect of PTAB decisions is the ability to move on and challenge them in the courts under the Administrative Review Act. This requires PTAB to build a record for its decisions that can be judicially reviewed. Smaller cases go to circuit court while the largest cases are appealed directly to the appellate courts. Relatively few cases are challenged, less than 1 percent of all decisions, according to PTAB data.

Like many other tribunals in Illinois, including the court systems and the Independent Tax Tribunal, PTAB communicates its findings to the public. It annually compiles a Synopsis of Relevant Cases broken out by different classes of property. Its decisions are also available on the PTAB and Illinois State Library websites. Interestingly, PTAB officials say they have seen little difference in the types of cases coming before the board as a result of those educational efforts.

Cook County and “Reform”

In 1996, as part of a larger “reform” package, PTAB jurisdiction was extended to Cook County. Other pieces of the reform replaced the Board of (Tax) Appeals in Cook County with a three-member Board of Review, elected by district, and eliminated the highly restrictive “constructive fraud” standard for challenging assessments. Under that standard the only appeal from a Board of Appeals decision was to court where the property owner had to prove that an assessment was so bad it amounted to fraud. At about the same time the Property Tax Extension Limitation Law (better known as Tax Caps) was extended to Cook County.

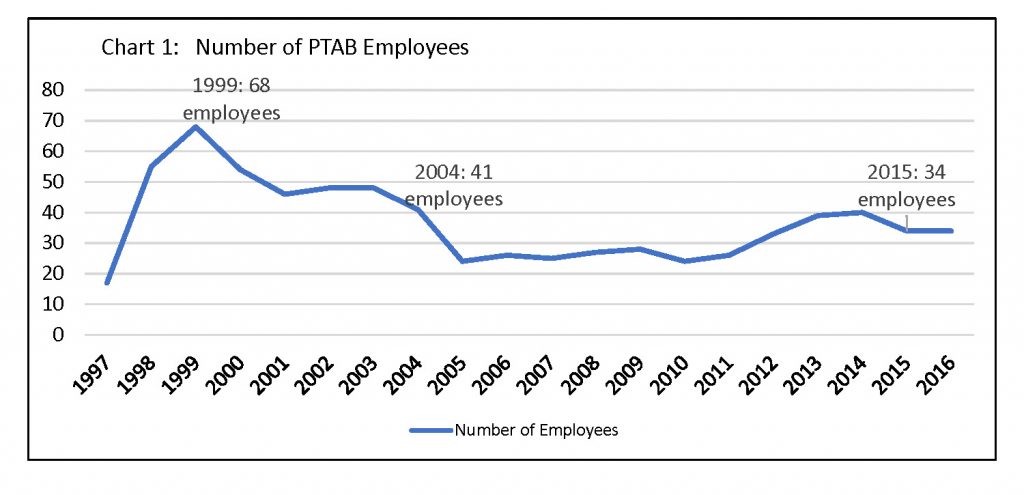

One of the concerns expressed by Cook County officials was that PTAB would be overwhelmed by assessment appeals and that taxing districts would see delays in receiving revenues. To avoid that, staffing at PTAB was dramatically increased from 17 in 1996 to 68 in 1998. The assumption was that PTAB would see 40,000 appeals, based on the number of cases handled by the Board of (Tax) Appeals, but the cases did not initially materialize and employees were loaned to other agencies. Then, as the state experienced financial problems, headcount was slashed in 2004 and 2005, just as appeals from Cook County were skyrocketing. See Chart 1.

A long-standing complaint from lawyers who practice before PTAB has been the heavily manual process involved in filing an appeal, including filing applications in triplicate. The bar associations have advocated for increased electronic filing, a streamlined process for relatively small residential challenges, and expediting settlements between the parties.

The agency is taking steps to automate and streamline its processes. It has an online system that taxpayers and Boards of Review can use to track their cases and PTAB personnel can access records online. The agency is taking steps to interact with attorneys and boards of review electronically and has proposed rules to reduce the number of copies that must be filed. They are also preparing to hire another ALJ and a couple of appraisers and are increasing use of retired employees on 75-day contracts.

The Backlog by the Numbers

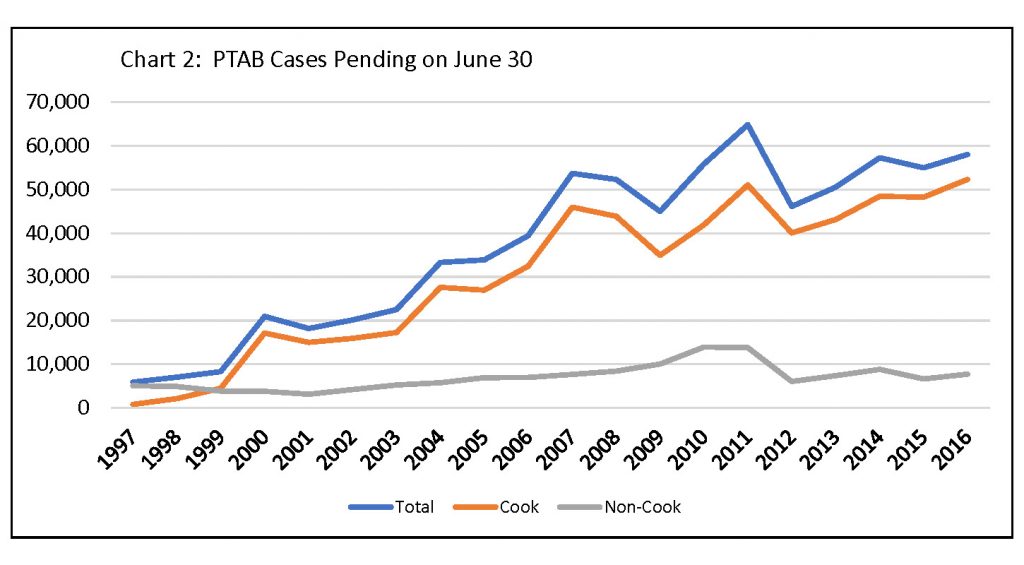

In terms of cases in backlog, appeals from Cook County have accounted for the increase. See Chart 2. While downstate cases included in the backlog have remained relatively steady, the Cook portion of the backlog has grown dramatically. A 2003 legislative proposal to limit PTAB authority to residential properties of six units or less (Class 2) in Cook County failed to pass, but positions were cut as if it did. Cook County has almost half of the state’s population and taxable value, but accounted for 78 percent of all appeals to PTAB last year.

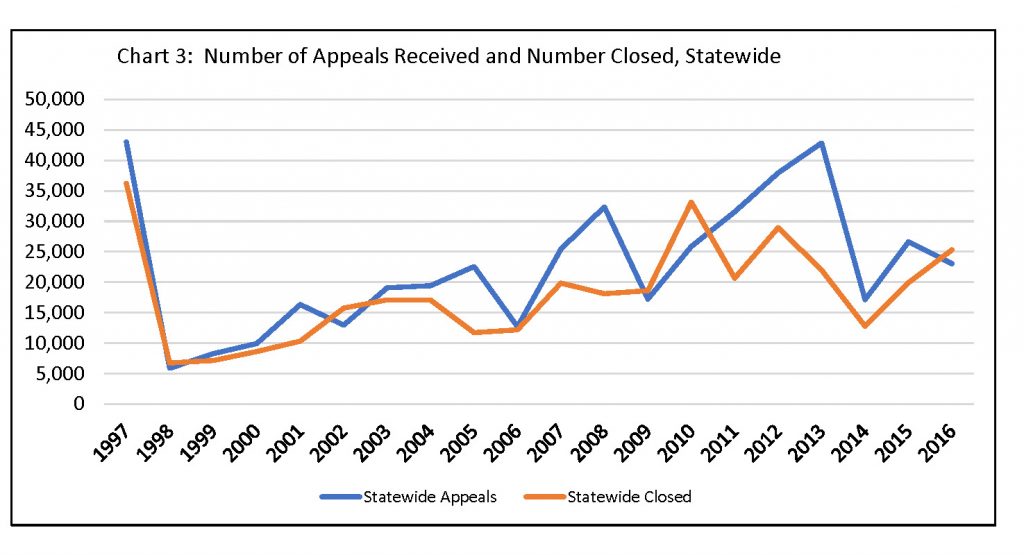

PTAB’s automation efforts and emphasis on settlements have shown some positive results. While the backlog has grown, the number of cases closed by PTAB each year has also increased steadily. The red line on Chart 3 shows the Board closing more than 20,000 cases in the last two years. The trend continued for the two years not yet audited, with 31,511 cases closed in 2017 and 28,304 closed in 2018 but new cases docketed grew even faster so the backlog also increased.

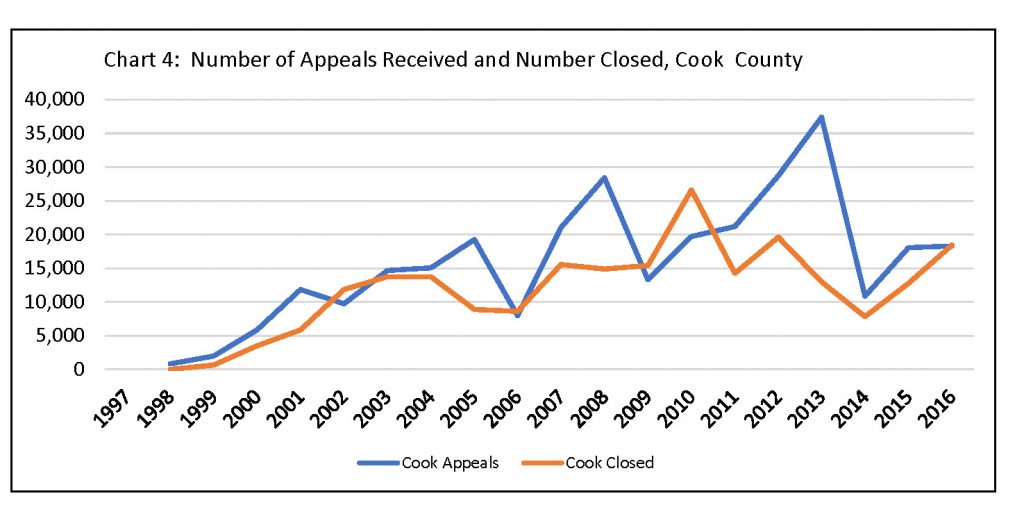

Chart 4 provides a visual of how Cook County appeals to PTAB spiked during the real estate crash that began in 2008. That was a period when, particularly in Cook and the Collar Counties, home values which had been soaring declined significantly and homeowners saw their property tax bills rising while their home values dropped. The chart shows how the gap between Cook County appeals and Cook County cases closed grew in that period, creating the increased backlog illustrated above.

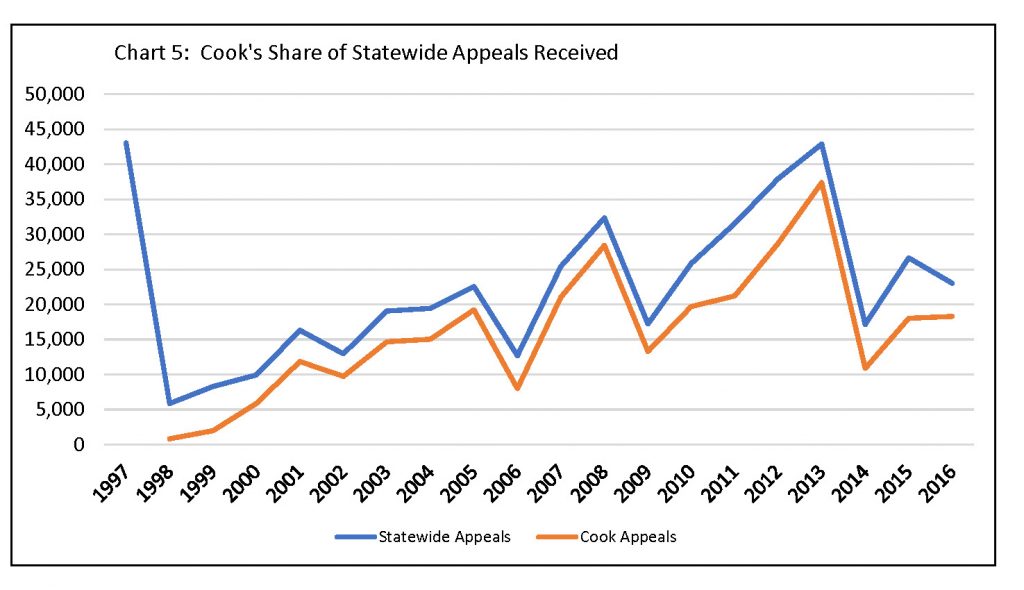

Finally, Chart 5 illustrates the extent to which Cook County drives the statewide numbers. When appeals from Cook County increase, the statewide total increases; when new Cook Cook appeals decline, the statewide total declines.

Conclusion

In Illinois the property tax is by far the largest single source of total state and local government tax revenue – and the largest single source of tax complaints. The Property Tax Appeal Board provides a needed option for disputing an assessment, but when that system does not fulfill its mission – for whatever reason – the problems caused for both taxpayers and local governments undercuts the benefits of the independent review.

The growing backlogs are no secret, having been identified by the Auditor General for 14 years. PTAB needs to operate efficiently and is to be commended for efforts to streamline its procedures, but more is needed. There must also be recognition that de novo reviews require resources. Increasing appeals from Cook County still have not reached the estimates made before PTAB jurisdiction was extended there, more than 20 years ago.

[1] Mike Klemens, President of KDM Consulting Inc., does tax policy research for the Taxpayers’ Federation.