Enterprise Zones in Illinois – The Economic Impact is Still Unknown – Dr. Natalie Davila

Enterprise Zones in Illinois – The Economic Impact is Still Unknown

November 2018 (71.10)

Dr. Natalie Davila

Dr. Natalie Davila is an economist with an extensive background in public finance. She was Director of Research for the Illinois Department of Revenue for 10 years.

In a previous Tax Facts article discussing the evaluation of tax incentives (September/October 2016 Tax Facts (69.5)) we highlighted that, based on research from the Pew Charitable Trusts, Illinois was the only Midwestern state categorized as ”trailing” (as opposed to “leading” or “making progress”) when it came to reviewing and evaluating tax incentive programs. Pew has identified best practices states should employ to measure economic impact of these programs and to inform policy makers’ decisions; Illinois had not consistently adopted these practices.[1] However, at that time Illinois was in the process of putting reforms to the Illinois Enterprise Zone program in place. Extensive reporting requirements were part of this reform, with the goal that this data would be used to evaluate the program.

During the 2012 spring legislative session there were frequent discussions expressing concerns about the accountability and effectiveness of the State’s Enterprise Zone program, including threats to end the program. Public Act 97-0905 was the end result of those discussions: the program was preserved, but reformed. This reform legislation included new Enterprise Zone designation requirements, establishment of an Enterprise Zone application review process, and new reporting requirements for businesses receiving Enterprise Zone benefits.

There are two incentives available to businesses in Enterprise Zones that require certification by the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity (“DCEO”): the expanded sales tax exemption for manufacturing machinery and equipment and the utility and telecommunications tax exemption. In order to receive these exemptions DCEO must certify that the business meets certain investment and job creation/retention criteria.

There are additional Enterprise Zone incentives that do not require certification:

- Sales tax exemptions on all building materials

- Income tax credits for investments in qualified property

Local governments may offer local incentives to encourage business development in Enterprise Zones, most notably property tax abatements or (in Cook County) assessment reductions. Local governments also frequently waive permit fees for projects in Enterprise Zones.

In addition to the application process, businesses in Enterprise Zones are now required to report annually on the total tax benefits received by incentive category, job creation, job retention, and capital investment. The Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity (DCEO) makes this information available by zone as part of their Annual Report on the Enterprise Zone program. Proponents of the legislation argued that this required reporting would provide additional data for policymakers to evaluate economic development incentives provided to businesses through Enterprise Zones.[2] These measures were expected to be the first step toward making informed policy decisions on the effectiveness of the Enterprise Zone program. [3] While a move in the right direction, this reporting requirement falls short of the Pew criteria in several ways including that it relies solely on self-reporting. However, more importantly, at the time of writing the data has not yet been used to conduct either an economic impact study or economic evaluation of the program.

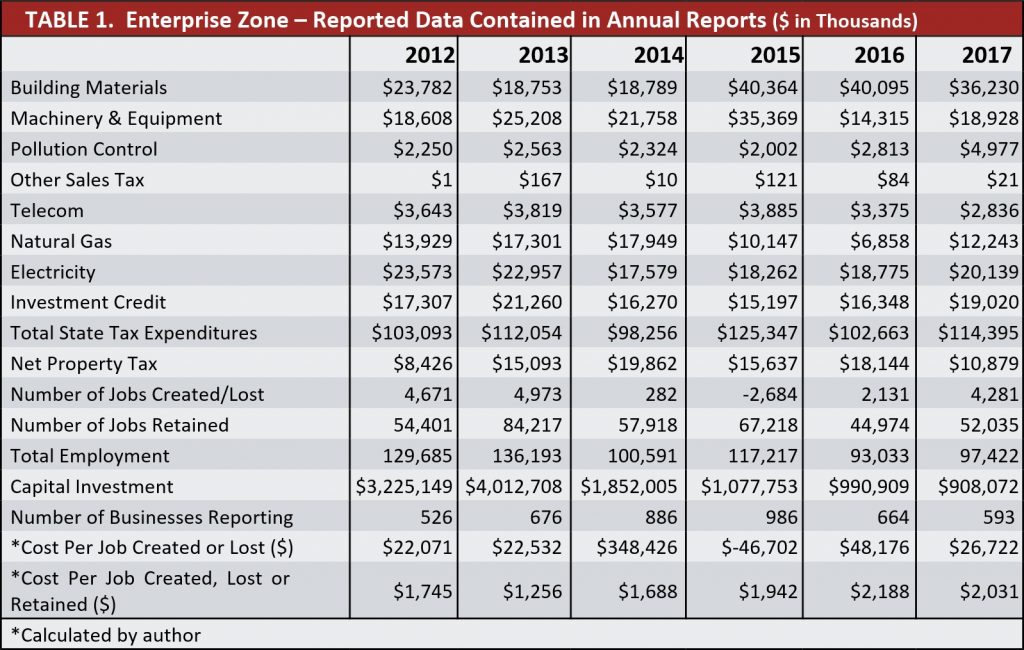

We now have six years of self-reported data to analyze, although as Table 1 below shows, the publicly-available data is difficult to evaluate and surely reflects a combination of incomplete reporting and user error or confusion. In our 2016 article we found that, while Enterprise Zone reporting had improved, it lacked quality control and suggested that the Audit Bureau of the Illinois Department of Revenue (“IDOR”) review the incentive data as part of the audit process. Upon reflection, we now suggest IDOR’s research office take the lead in improving data quality control, including a review of the self-reported data to allow for timely data quality improvement. We do not believe that businesses are intentionally misreporting, but instead may not have clear ideas of what they should be reporting, so this approach is more aligned with the functions of the two groups within IDOR. Timely feedback could help improve the quality of the data and therefore a more reliable analysis will result. For example, IDOR staff could take a sample of companies submitting information on the Enterprise Zone reporting web site and verify the information through a combination of examining tax return data along with in person interviews. The self-reporting requirement is still fairly new, and not all benefit recipients may be reporting the data in the same way, and some may still be unaware of the reporting requirement. This would not be conducted as a tax audit, but as part of the economic analysis of the program. This sample would be stratified by geographic location, company size, industry and type of incentive. Deviations in information identified through this process could then be used to make modifications to the population of self-reported data. Once a relatively reliable data series has been developed, the next phase would be to develop a methodology that would permit statistical analysis that isolates the impact of being located in an Enterprise Zone and receiving tax incentives versus being in a geography where the tax incentives were not available. Development of such a methodology should be based on existing research approaches combined with input of local academic experts.

Table 1 illustrates that while the total state tax expenditure reported is relatively consistent, reported job data reported varies considerably from year to year. For example:

- The number of jobs created/lost ranges from 4,973 jobs created in 2013 to 2,684 jobs lost in 2015.

- The number of jobs retained ranges from 44,794 to 84,217

- The state tax expenditures (cost) per job created/lost ranges from $348,426 to -$46,702. This negative number is due to a net loss of jobs in 2015.

- The state tax expenditure (cost) per created, lost, or retained job ranges from $1,256 to $2,188

- The number of jobs created, lost, and retained as a percentage of total employment ranges from 45.6 percent in 2012 to 65.5 percent in 2013.

Without any interpretation of the data by IDOR or DCEO it is difficult to determine whether economic factors are behind these variations or whether they can be attributed to the lack of quality control. In addition, without performance benchmarks it is not possible to determine whether or not the program is meeting its goals. For example, what cost per job created/lost should be considered a success?

The Annual Report does not outline what kind of quality control takes place once businesses self-report the data. We submitted questions to IDOR to attempt to shed some light on this process. Of particular concern is the reliability of the estimate of retained employees. Guidance provided by IDOR says that “Current employees are not automatically retained employees. Rather, there must be some indication that the business was going to close or eliminate employees for the employees to be counted as retained. “[4] This can easily be interpreted differently by different businesses. Based on conversations with IDOR no documentation is required to justify the number of retained employees claimed by businesses. As calculated in the above table, the reported data means that between 45.6 percent and 65.5 percent of all jobs in EZ firms are created and retained as a result of EZ tax incentives, which on its surface seems unlikely. Documenting whether jobs would be lost but for the incentive is a difficult if not impossible task. Also, since there are no performance measure guidelines associated with program success the reporting of these numbers is in some sense meaningless. We suggest that IDOR and DCEO work with the business community to figure out what measures would be more useful, and more realistic for business to comply with, to help to determine if the program is meeting its goal(s).

One item that was thought would increase compliance was the imposition of penalties. Proposed rules setting forth penalties for non-compliance with EZ building materials reporting became final on October 22nd 2015.[5] With only two years of post-penalty data available, we do not see any increase in reporting.

One other issue that was brought to our attention by IDOR staff is that data in the Annual Report is not necessarily the most up-to-date/comprehensive data reported to and by IDOR. IDOR has a deadline by which they have to report data to DCEO – which they comply with – but they receive many additional and amended reports after this date. We suggest that IDOR continue to provide DCEO with preliminary data (to be in compliance with the law) but that DCEO also publish final data. While the preliminary data provides more timely information, the final data provides a more complete picture and allows for accurate annual comparisons over time.

When it comes to evaluating the Enterprise Zone program we are left scratching our heads. When the 2012 legislation was being considered, discussions on evaluating the program concluded that IDOR should take the lead on such an endeavor as they would have direct access to the individual business data and as such would be in a position to conduct analysis and comparisons based on various characteristics (identified above). However, the law gives DCEO this responsibility. It is our understanding that at the time of writing DCEO has not requested access to the necessary information. That access may not even be possible, to the extent it comes from income tax returns subject to the IRS’ strict information-sharing limitations.

In conclusion, given that the law requires that the tax incentive data be used to evaluate the EZ program and given that almost 3,000 businesses are spending a not insignificant amount of resources to comply with the law, we recommend that IDOR start to put in place quality control processes and procedures so this data can be used to conduct a reliable evaluation of the EZ program.

[1] Pew periodically updates its state-by-state review of incentives review practices, at https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/05/how-states-are-improving-tax-incentives-for-jobs-and-growth

[2] http://www.cmap.illinois.gov/about/updates/-/asset_publisher/UIMfSLnFfMB6/content/enterprise-zone-extension-and-reforms-signed-into-law

[3] http://www.cmap.illinois.gov/about/updates/-/asset_publisher/UIMfSLnFfMB6/content/enterprise-zone-extension-and-reforms-signed-into-law

[4] https://www2.illinois.gov/rev/businesses/incentives/Pages/reportingfaqs.aspx#qst6

[5] https://www2.illinois.gov/rev/research/legalinformation/regs/Documents/part130/130-1951.pdf#search=130%2E1951%28g%29

TFI is not the only organization supporting the periodic evaluation of tax incentives. For example, for many years the Civic Federation has recommended that the State develop a comprehensive economic development plan in accordance with the best practices established by the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) and embraced by the Pew Charitable Trusts.[1][2] For Enterprise Zones this would mean:

- Common goals, including: targeting specific economic sectors, business retention and/or recruitment, geographic focus, job creation, blight mitigation, improving economically distressed neighborhoods, and environmental improvements. Many of these factors are part of the Enterprise Zone application and reporting process in Illinois. However, there are no guidelines (performance measures) on what levels are considered successful and what levels are not.

- Evaluation activities and factors, which should include: how a proposal measures up to established economic development criteria; a cost/benefit analysis; analysis of the impact of a project on existing businesses; and a determination of whether the project would have proceeded if the incentive is not provided. Without this type of analysis, there can be no meaningful evaluation of Illinois’ Enterprise Zone program.

- Performance standards, to help a jurisdiction gauge the effectiveness of its overall economic development program. Once these measures are established, a process should be established for regular monitoring of the economic development incentives granted and the performance of each project receiving incentives. This process should also identify where responsibility for monitoring and compliance lies within the government structure and identify appropriate staffing levels to make sure the activity can be carried out.

The topic is gaining attention around the country; in October of this year, the National Conference of State Legislators hosted a Roundtable on Evaluating Economic Development Tax Incentives, with presenters from a variety of states, non-profit organizations, and academia.[3]

[1] https://www.civicfed.org/civic-federation/blog/new-state-law-aims-reforming-economic-development-incentives

[2] http://www.gfoa.org/economic-development-incentive-policies

[3] www.ncsl.org/research/fiscal-policy/2018-roundtable-on-evaluating-economic-development-tax-incentives.aspx

Illinois is Not Alone

Evaluating Enterprise Zones is not easy and is subject to many uncertainties and assumptions. For example a 2013 report evaluating EZs in Maryland issued by Maryland’s Department of Legislative Services Office of Policy Analysis found “The Department of Business and Economic Development and the Comptroller’s Office Do Not Assess the Effectiveness of the Enterprise Zone Tax Credit”.[1] These two agencies are required by law to annually assess the effectiveness of tax credits provided to businesses in Enterprise Zones, including the number and amount of credits granted and the success of the tax credits in attracting and retaining businesses within Enterprise Zones. While the Department of Business and Economic Development (DBED) tracks the number and amount of credits granted annually, it does not have a framework or metrics in place for measuring the actual effectiveness of the credit. There is also a lack of accurate data on the change in employment and number of businesses within Enterprise Zones, which makes assessing the impacts of the credit very difficult. The evaluation report contains three recommendations for DBED, in consultation with the Comptroller’s Office, the State Department of Assessments and Taxation , and local jurisdictions: 1) adopt formal metrics and a framework for analyzing the cost-effectiveness of each Enterprise Zone and its effectiveness in attracting businesses and increasing employment; 2) identify clear outcomes and determine quantifiable measures, which could include project evaluation, employment trends, impacts on poverty and population, private-sector investment in communities, and overall community revitalization; and 3) adopt procedures that will facilitate more accurate collection of Enterprise Zone data to enable evaluation of the program

[1] http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/pubs/budgetfiscal/2013-evaluation-enterprise-zone-tax-credit-draft.pdf

A Possible Way Forward

Once Illinois has implemented some data quality control measures we suggest employing a research approach similar to the one used in a 2004 study of California’s Enterprise Zones. [1]

In a report by the Public Policy Institute of California published in 2009, researchers used the National Establishment Time-Series (NETS) database, which provides employment and exact location data for nearly all business establishments in California from 1992 to 2004, along with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to extract employment data by firm that corresponds with firms within Enterprise Zones. These databases, combined with spatial and statistical methods (see the report for more detail), allowed researchers to overcome important limitations of previous research on the effects of Enterprise Zone programs. Their approach allowed for the construction of appropriate control groups for comparison and allowed the authors to estimate the effect of the program on employment. In addition, the researchers also conducted interviews with local administrators of the Enterprise Zone program. In these interviews, they asked about the goals of the program, the activities of local zone administrators, and the main challenges they face, among other questions. These responses were used to supplement the business establishment data in the NETS to assess whether local zone activities influence the effect of the program on jobs.

In this particular study the authors found that, on average, Enterprise Zones had no effect on business creation or job growth. However, they did uncover findings and made recommendations that may be useful in making Enterprise Zones more effective. For example, they found that the program’s effectiveness differs across zones, appearing to have a more favorable effect on job creation in zones with smaller employment shares in manufacturing and in zones where the administrators report greater marketing and outreach activity. As a result, they recommended that the state should evaluate individual zone success with consistent evaluation metrics; this is an essential step for judging which factors make some zones more effective than others.

[1] http://www.ppic.org/content/pubs/report/R_609JKR.pdf

Behind the Numbers

Each year, as required by law, the Illinois Department of Revenue has submitted information about the prior year’s Enterprise Zone tax benefits to DCEO. Each year, DCEO takes that information and includes it in a report, available on the DCEO website, as required by law (although publication dates often lag the statutory due date). From even a cursory look at that data, included in Table 1 above, it is obvious the data has problems. Each year IDOR submissions have acknowledged that there are limitations to the data accuracy and that compliance levels and verification procedures were expected to improve in the future, using nearly identical language year after year after year.

Occasionally, the IDOR cover letter contained in the DCEO annual report has described some of the measures taken to improve accuracy: checking data against other available sources of information, including reports submitted by utilities and purchasers of building materials; consulting with county clerks regarding property tax abatements; and conducting follow-up interviews with business representatives.

We reached out to IDOR to find out more details on their verification and data quality improvement processes. They responded as follows: “With regard to the Building Materials sales tax exemption reporting, failure to file the required reports can, and has, led to revocation or suspension of their exemption certification. With regard to report accuracy, EZ credits and deductions claimed by a taxpayer are reviewed as part of our normal taxpayer audit process”. While this is a good first step, not all businesses are audited, meaning a significant population of businesses’ information is not reviewed. IDOR also shared with us that since 2016 they have begun sending annual notices to all known EZ businesses reminding them of their reporting obligations. Building material certificate holders are sent a series of reminders before taking action to revoke their certificate. IDOR also works closely with the Enterprise Zone Association and with individual Zone Administrators to encourage reporting compliance—including providing zone administrators with a list of known businesses in their zone so that the zone administrator can assist in identifying taxpayers required to report. And finally, IDOR is in the process of completing GIS mapping of all zones and populating each zone with all known businesses to ensure IDOR has the greatest outreach.

Each of these steps should lead to improved data quality and help make meaningful evaluation of the Enterprise Zone program possible.