A New Property Tax Relief Tax Force: Same Old Problems – Mike Klemens

A New Property Tax Relief Tax Force: Same Old Problems

August 2019 (72.6)

By Mike Klemens*

In the closing days of its spring 2019 session, the Illinois General Assembly created a Property Tax Relief Task Force to identify ways to create short and long-term relief for homeowners. Illinois has seen a number of these commissions, and much of the reaction to this one was “here comes another report to sit on the shelf.” Reviewing previous reports leads to a simple conclusion – property tax relief is hard to accomplish, and this is a particularly challenging time to try.

National Context

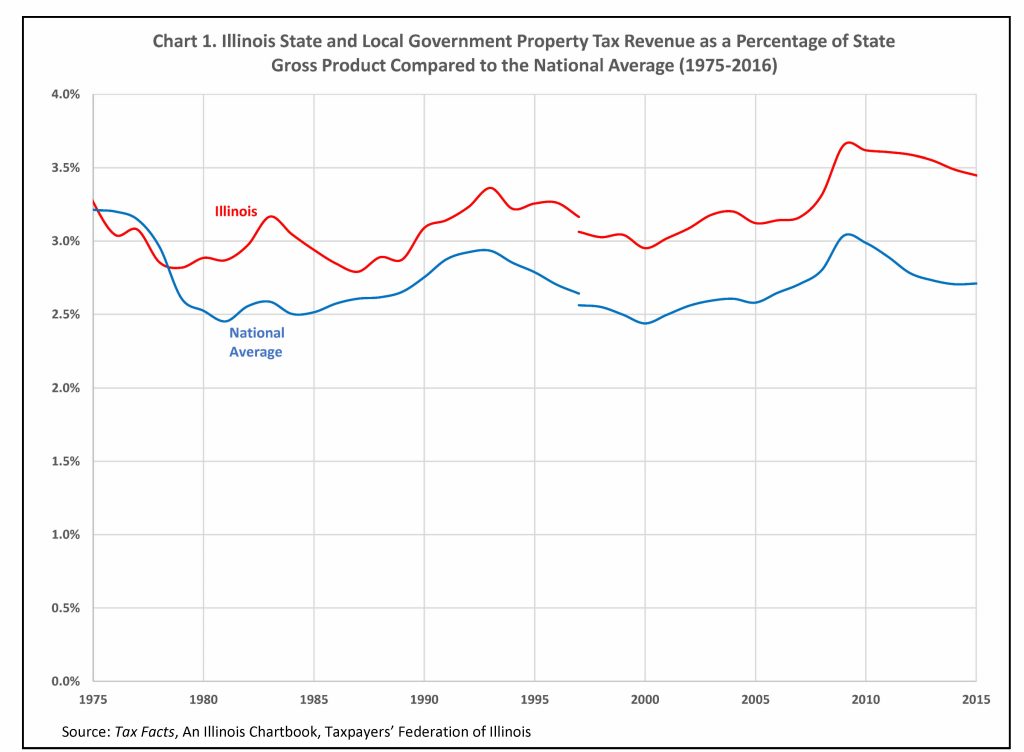

Let’s start by examining where Illinois stands in terms of property taxation, compared to other states. Chart 1 compares Illinois property taxes as a percentage of the state’s economic activity to other states. Since the late 1970s, Illinois’ property tax burden has been above the national average and the gap between Illinois and the national average has widened since the 2008 real estate crash. Still, the graph shows Illinois tracking the national trend.

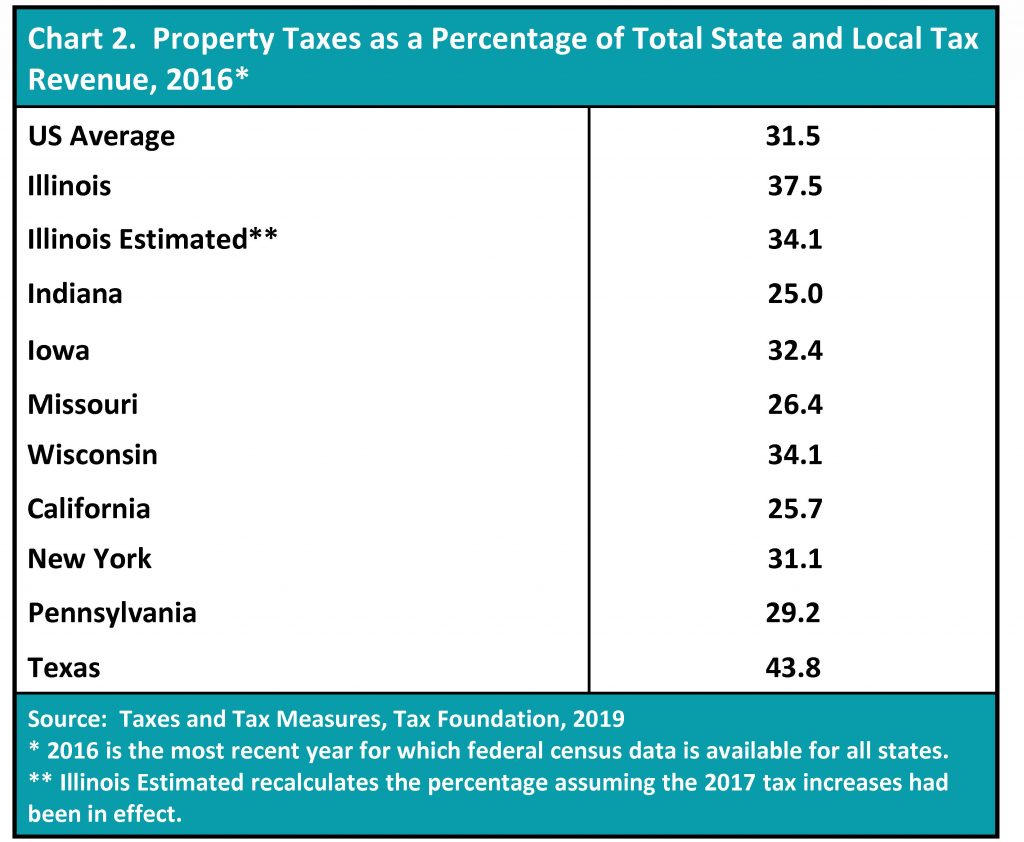

One reason for Illinois’ above average property taxes is apparent in Chart 2, the relative shares of Illinois state and local tax collections. Of the total taxes collected by Illinois state and local governments, 37.5% was property tax. The national average was 31.5%, and although 10 states were higher than Illinois, that included states with no income tax – Alaska, New Hampshire, Texas and Wyoming – and two – New Hampshire and Montana – with no sales tax.

In 2016 Illinois’ “roller coaster” income tax rates were at a low point. Had the current income tax rates been in effect, property taxes would have accounted for 34.1% of state and local government taxes, still above average but with only 15 states higher than Illinois. Because we are looking at relative shares, that improved standing doesn’t mean property owners saw any relief, just that they are paying more non-property taxes. If voters were to approve the proposed graduated income tax, the property tax share of Illinois’ tax burden would fall further.

What’s Happening in Illinois Today?

After losing 23% of its value during the real estate crash between 2009 and 2013, the statewide property tax base is again growing, though total statewide taxable value is still well below its 2009 peak. Even as values were falling, property taxes paid were increasing, but modestly. For the latest three years for which data is available – taxes paid in 2016-2018 – the annual growth in statewide property taxes billed has exceeded $1 billion annually – returning to pre-crash levels. The result: property values are still below their peak, but tax bills are higher than before, and increasing.

Chicago has seen significant property tax increases recently, to cover pension costs. In most Chicago neighborhoods, the average homeowner has seen property taxes increase 60% over the last four years (taxes paid in 2016 to 2019).

Previous Illinois Task Forces

Furman Commission – 1982

There has been no shortage of studies that sought to find ways to provide property tax reform/relief. In 1982 Governor James R. Thompson created the Tax Reform Commission to examine the state’s overall tax structure. It was commonly known as the Furman Commission, named for its chairman James Furman, executive vice-president of the MacArthur Foundation. In the property tax world, it recommended:

- full valuation of property,

- installment payments,

- sunsetting of exemptions, and

- reformed school financing to infuse more state revenues into school funding.

None of its property tax recommendations were immediately implemented.

Ikenberry Commission – 1996

In 1996, Gov. Jim Edgar appointed the Governor’s Commission on Education Funding, better known as the Ikenberry Commission, after its chairman Stanley O. Ikenberry. The centerpiece of that effort was the replacement of local property tax revenues with state income tax funds. The legislation that came out of that commission’s work stalled, at least in part when lawmakers recognized that for some residents the income tax increases would exceed the property tax savings. See “Replacing School Property Taxes: A Bigger Challenge Today,” Tax Facts, February 2019.

Bramlet Commission – 1998

Two years after the Ikenberry Commission-inspired legislation failed, Gov. Edgar tried again and appointed the Gov.’s Commission on Property Tax Reform, called the Bramlet Commission after its chair, TFI President Tim Bramlet. The commission concluded that “the charge of developing a simple ‘tax swap’ proposal that is fair and equitable to all taxpayers is not possible until certain state and local tax policy issues are addressed.”

The Bramlet Commission held to the Ikenberry Commission’s principles that property tax relief should be noticeable to property owners and pegged the number at $2 to $2.5 billion. (An equivalent number today would be $5 to $6 billion.) Perhaps learning from their predecessors, they wrestled more extensively with the practical implications of the “swap” than did the Furman or Ikenberry commissions and could not find a solution that did not create both “winners” and “losers.”

Among the tax policy issues impeding a tax swap that they identified were:

- A property tax base, exacerbated by the Cook County classification system, where businesses pay a higher percentage of property taxes than do homeowners, meaning a straight income-for-property tax swap would benefit businesses to the detriment of individuals.

- Concern that over time the relief granted to property owners would be eaten up by increases in property taxes.

- Geographic imbalances in property tax reliance would create winners and losers.

- Proliferation of local governments that makes it difficult to control local government spending.

- Reduced public pressure for reform. “The great political pressure for property tax reductions once felt in Illinois’ atmosphere has dissipated over the last few years.” Note: It’s back.

Link Task Force – 2009

One of the most recent efforts was the 2009 Property Tax Reform and Relief Task Force, created by the General Assembly in 2007 and chaired by Sen. Terry Link, and charged to “conduct a study of the property tax system in Illinois and to investigate methods of reducing the reliance on property taxes…” That report began with a section entitled “Back to the Future,” that went well beyond pointing out the numerous studies that had not been implemented. Quoting from a paper entitled “A Brief History of the Property Tax” presented in 2004 it noted, “citizens complained that real and personal property taxes were too high and demanded that the government lower expenditures. The tax assessment system was also perceived as biased and inefficient compared to the earlier standards set by Aristedes.” Although the message may sound like contemporary Illinois, the citizens were Athenians paying property tax in Greece, in 500 B.C.

The recommendations in the 2009 Task Force Report included:

- Correcting overreliance on local property taxes by rebalancing revenues raised by property, income and sales taxes.

- Consolidation of local government services.

- Enactment of a more robust circuit breaker program that would cover property taxes that exceeded a certain percentage of household income. They suggested that the current homestead exemptions, property tax credit on the income tax, and senior citizen assessment freeze homestead exemption programs could be subsumed into the circuit breaker, and

- Increasing the professionalization of individuals involved in valuing property for tax purposes.

Prospects for 2019 Task Force

Unavailable to the new commission is the most common element of the previous tax reform/relief studies – the recommendation to replace local property taxes with state revenues, primarily the income tax. That was an easy proposal to make – though clearly not an easy one to accomplish – when Illinois income taxes were significantly below national averages. With the 2017 rate increases Illinois income taxes are now above average, and the projected increases associated with the graduated income tax proposal will, if passed, raise Illinois even farther in most rankings. (While there are some who believe the $3.2 billion in new income tax receipts should be used to fund property tax relief, there are many other proposed uses of that money.)

Still around is one of the biggest problems that previous study groups have confronted: geographic differences in property values across Illinois, and particularly the dual tax systems that classifies property in Cook County but nowhere else in Illinois. Classification has historically benefited Chicago homeowners, the taxpayers who are now seeing some of the biggest property tax increases.

The pressure for property tax relief will push the task force to find ways to do so. One discussed proposal is a freeze for property taxes, which are growing state-wide by just over $1 billion (3.5 to 4 percent) annually. A one-year freeze would cost $1 billion, but a more noticeable two-year freeze would cost $3 billion, and a three-year freeze would cost $6 billion. That’s a lot of replacement revenues or local government spending cuts. And freezes presumably thaw.

Homestead Exemptions—tempting, but not actually helpful

Another popular program likely to be considered are increased homestead exemptions, which have the advantage of generally not costing the local government anything. That’s because they don’t cut taxes; they just shift the burden from homesteads onto non-homestead properties.

Homestead exemptions – reductions in the amount of taxable value taken before the tax rate is applied – have proliferated in Illinois, and today there are ten separate homestead exemptions. The largest are: the General Homestead Exemption, a $10,000 EAV reduction in Cook and $6,000 in other counties; the Senior Citizen Homestead Exemption, an $8,000 reduction in Cook County and $5,000 elsewhere; and the Senior Citizen Assessment Freeze Homestead Exemption. Homestead exemptions accounted for 5% of gross Cook County EAV in 1999, and grew to 9.25% by 2017. A 2010 report by the Civic Federation titled “Recommendations for Reform of the Cook County Property Tax System” stated that exemptions were undermining the tie between property value and property tax, and that it was time to curtail them and move toward a “truly ad valorem tax.”

For more detailed examinations of how homestead exemptions shift tax burden and do not cut taxes see, “Examining the Effects of Increased Homestead Exemptions,” Tax Facts, April 2017 and “Homestead Exemptions: Shifting Burdens, Not Cutting Taxes, Tax Facts, September/October 2015. As Nathan Anderson and Therese McGuire wrote of exemptions and credits in a working paper for the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, “Tax relief to some is not tax relief to all: tax relief to some is often tax increases for some others.”

Circuit Breakers—targeted relief, but costly

Given the high cost of property tax relief and other demands for limited state resources, the 2009 Link Task Force’s recommendation to expand the Circuit Breaker program may be an appealing, but still costly, option. Circuit breakers are programs that kick in and provide benefits when property taxes exceed a certain percentage of income. At the time of the task force report, the Illinois Circuit Breaker was providing $47 million per year in property tax relief grants to low income homeowners and renters. Two years later, on July 1, 2012, the program was terminated for lack of funding.

The Task Force found that the then-existing Circuit Breaker offered the most effective program to deal with high property taxes for households with low income: “An expanded program could target more assistance to those households where the tax burden (as measured against household income) is greatest and, as a grant program, would not shift the local tax burden to non-residential property.” The report also suggested the Circuit Breaker be in the form of a voucher to pay property taxes so that recipients experienced relief from their property tax bills.

The task force had the Department of Revenue run simulations using income tax return data where property taxes exceeded either 5 or 6 percent of income and with grants capped at various amounts between $750 and $1,500. The costs were between $1 and $2 billion, well in excess of the then-current program that was limited to seniors and disabled persons with very low incomes. To pay for the program the Task Force suggested adjustments to non-means tested programs like the property tax credit on the income tax, homestead exemptions, and the Senior Citizens Assessment Freeze.

A year later the Civic Federation also recommended that homeowners’ property tax relief, if desired, be provided through an expanded, means-tested, state level circuit breaker program. Their report saw the circuit breaker as an effective way of targeting property tax relief to the most needy. They suggested funding it by eliminating the state’s income tax credit for residential property taxes.

Support for circuit breakers also comes from Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy which, in a 2018 policy briefing, cited the benefits of targeting relief to low-income taxpayers and introducing an “ability to pay” concept to the property tax. Its downsides were the separate application process and the need for an outreach program.

A final advocate for circuit breaker programs is the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, in a 2009 report entitled “Property Tax Circuit Breakers: Fair and Cost-Effective Relief for Taxpayers.” The report noted that many tax relief efforts invoke cases of problems for low-income homeowners and then enact programs that offer tax relief to all. The report estimates that a well-designed system would cost about 6 percent of property tax revenues, roughly $2 billion in Illinois’ case.

Procedural Improvements

Given the high cost of any meaningful tax reduction options, the 2019 task force may find its most productive area of inquiry, and opportunity for change, to be improving the property tax process. For example, would taxpayers (and taxing jurisdictions) benefit from paying property taxes in more than just two installments a year? Are there more efficient ways to assess, levy, and collect this tax?

The backlog at the state Property Tax Appeal Board is notorious: the Civic Federation put the backlog of cases at 62,077 at the end of State fiscal year 2018. See “PTAB: Struggling to Remain Afloat in a Sea of Appeals,” Tax Facts, September 2018. Giving the Board resources to eliminate its backlog of appeals, or changing its responsibilities to reduce its workload, would make the property tax system work better. In June the Civic Federation released a study that found PTAB was underfunded, understaffed, and needlessly tied to procedures and rules that slowed its process. Proposed rule changes to streamline PTAB processes were developed by an ad hoc committee of the Illinois State Bar Association in 2013 and supported by the Civic Federation, Taxpayers’ Federation of Illinois and the Illinois Chamber of Commerce. While PTAB has made some progress, a number of recommendations still remain unadopted.

Conclusion

The members of the new Property Tax Relief Task Force face the same challenges as their predecessors. Chief among them are Illinois’ high reliance on property taxes to fund schools and local governments and the resulting high cost of providing across-the-board tax relief.

But they have some new challenges:

- Competition for funds needed for relief.

- Income tax rates that are no longer well below national averages.

- Pressure from Chicago homeowners whose bills are rising fast.

Perhaps the targeted relief of an expanded circuit breaker, as suggested by the 2009 Tax Relief Commission, can offer an opportunity for meaningful relief to at least some taxpayers. Procedural improvements, while less splashy, can also improve the taxpayer experience and confidence in the system.

* Mike Klemens, Founder of KDM Consulting Inc., does tax policy research for the Taxpayers’ Federation.